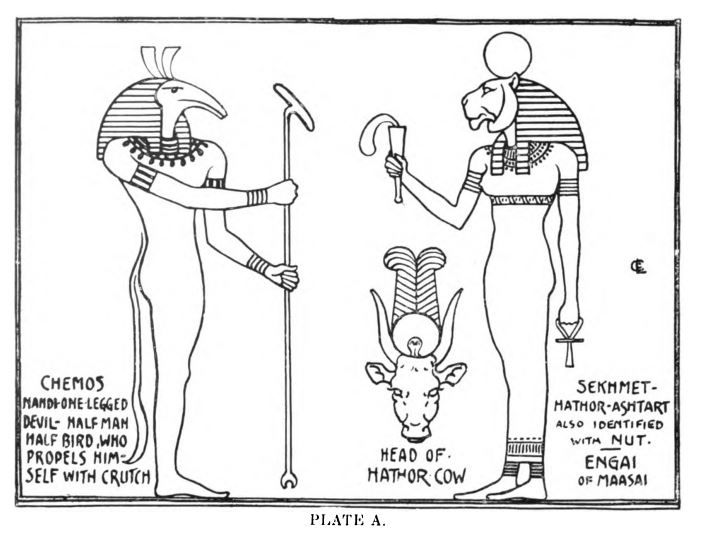

This post unearths valuable passages which I found in the following important book, and which shed light on Cram Cooper’s assertion that Sekhmet and Hathor are one and the same:

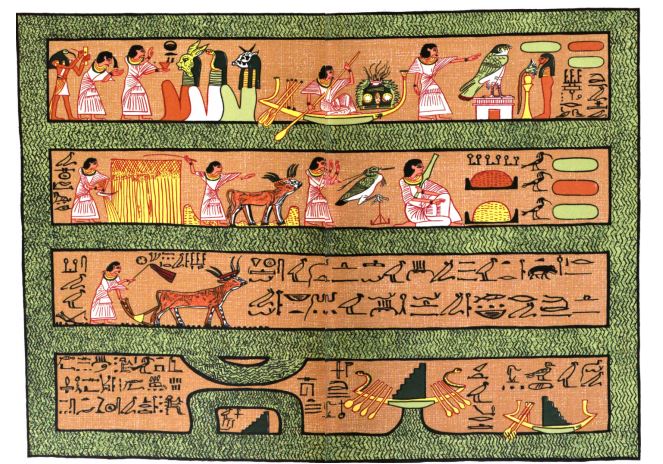

A Guide to The Antiquities of Upper Egypt, From Abydos to the Sudan Frontier, By Arthur E. P. Weigall, Inspector General of Upper Egypt, Department of Antiquities, Egyptian Government, with 69 maps and plans, New York, MacMillan Company, 1910, 626 pages.

This rather large tomb of priceless observations, of among other things, the temples of ancient Egypt, was produced around the turn of the previous century by Arthur E. P. Weigall (1880-1934), a man who worked alongside the infamous Flinders Petrie at the site of Akhenaten’s ancient city at Tell el-Amarnaat and then later assumed the position of Chief Inspector of Antiquities for Upper Egypt at Luxor at the slight age of 25. This was after Howard Carter’s resignation due to the Saqqara Affair.

Within this book’s spellbinding pages, there are many references to Egyptian goddesses and their appearance in the ancient temples and shrines. Of note, Weigall finds that the goddesses, that we all know and love, are often in such close proximity, as to assume eachother’s duties and positions. Of note, the goddess Sekhmet is mentioned 41 times, Mut, 62, Hathor, 371, and Isis, 448.

Below are just a few of the strongest examples of the codependent nature of the relationship, however, for a fuller understanding, you may want to read the entire book.

CHAPTER VI: THE TEMPLES OF KARNAK (pp 84 – 113)

On page 102, there is a direct reference to Mut taking on the form of Sekhmet in Hypostyle Hall. Hypostyle Hall is among the ruins at Karnak and believed to be erected by Nectanebo the First (B.C. 382-364).

The passage is as follows:

A doorway leading into the Hypostyle Hall is now passed, and

beyond it (28) there is a similar scene of the slaying of prisoners

before Amen. Next (29) at the bottom of the wall he presents

Hittite prisoners to a shrine in which are Amen- Ra, Mut, Khonsu,

and Maat. It should be observed that the goddess Mut has the

form of Sekhmet (see p. 112, where the subject of the identification

of these two goddesses a hundred years earlier is discussed).

Above this scene he presents Libyan prisoners to Amen- Ra, Mut,

and Khonsu.

This is a significant observation, and this, as well as other evidence, points to the idea that over time, Mut was merged with Hathor, Ra’s wife and mother of Horus. Mut later also became known as the Eye of Ra, which is the exact identity of Sekhmet.

Further, on page 112, during a description of The Temple of Mut in Asher, which dates from the reign of Amenhotep the III (B.C. 1411–1375):

The second doorway is then reached. On either side there is a figure of the bearded dwarf Bes, a god almost as closely connected with womanhood and maternity as was Mut herself. This gateway is said in the inscription to have been built by Amenhotep the Third and Rameses the Second, and to have been restored in Ptolemaic times. We next pass into the second court, around which are numerous seated statues of the lion-headed goddess Sekhmet, many of which bear the name of Amenhotep the Third, while others are dedicated by Pinezem the Second and Sheshonk the First. The goddess Sekhmet was the wife of Ptah, the great Memphite deity, and thus bore to him the same relationship that Mut did to Amen, the Theban god. She was identified with Hathor ; and there seems little doubt that she was also identified with Mut in some of her forms. In the reign of Amenhotep, the Third there was a tendency to introduce features of the religions of the north into the Theban worship. Rames, the vizir at the end of the reign (p. 160), seems to have been a Memphite noble; and it is known that the kings of this period themselves lived for part of the year at Memphis. The free introduction of these Sekhmet figures into the temple of Mut may thus be accounted for by the supposition that Mut of Thebes and Sekhmet of Memphis were identified as one goddess by those who were desirous of uniting the thought and policy of Upper and Lower Egypt (see also p. 162).

Again, a reference leaving no room for ambiguity, and from the period’s most impeccable authority. I think Cram Cooper may be on to something here. I still his sanity and the crazy story that he tells, which is how he arrived at this conclusion completely independently of any scholarly work.

One thought on “Sekhmet is Hathor: Evidence from Upper Egypt”

Comments are closed.